I’m moving again.

I didn’t think it would happen. I’ve moved across the country several times already, you might recall. But, like many Americans, I found a new job in a new city calling to me, and I answered the call.

We’re unusual in this way in the United States. We move from city to city more than almost any other developed nation—and most of those other nations have far less distance to travel.

We have a long history of mobility. It’s one of the advances that set the New World apart from the Old. Our founders wanted us to move. They didn’t want us confined to the class we were born into or the name we were given or the land our parents could bestow on us. They wanted us to set out across this vast continent, and they didn’t want us to settle until we found a home we could call our own.

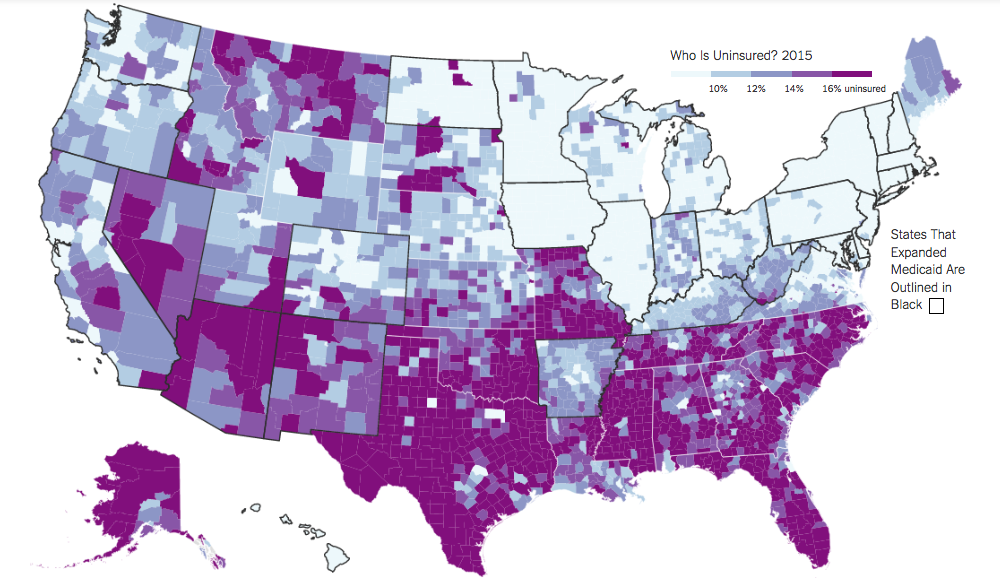

In recent years, that vision seems to have receded. The vast continent feels as if it has grown vaster. In so many ways, we appear to have grown apart: rural from urban, rich from poor, black from white, immigrant from native-born.

And so, it’s not surprising that we move less than we used to.

As mobility declines, so does our common understanding of each other. We learn less, we share less, and we empathize less. We come together less often, we bicker more frequently, and we get less done.

Moving isn’t for everyone. Many Americans are happy where they are, and they never want to leave. They are the bedrock of their communities. We would be poorer without their presence there.

But all Americans deserve the opportunity to find a place where they can flourish, a place where they truly feel home. As my colleague (and graduate student) Anthony W. Orlando has written and regularly reminds me, they deserve “a good job with good benefits in a growing economy where good schools and a safe neighborhood in a clean environment create real opportunity.” That is real freedom. That is the American dream.

“I don’t think we’ve done a very good job of defining the American dream in the 21st century and why equality of opportunity is so essential to it.”TWEET THIS

I don’t think we’ve done a very good job of defining the American dream in the 21st century and why equality of opportunity is so essential to it. Instead of framing a coherent vision, we’ve wound up blaming a long line of villains, some real, some imagined: bankers, politicians, minorities, refugees, liberals, conservatives, lenders, borrowers, Baby Boomers, Millennials…

And all the while, our public discourse has grown more toxic, our political institutions more gridlocked, and our worldviews more blinkered. If we continue down this path, the day will come when we have narrowed our field of vision so much that we can’t see anyone but ourselves anymore.

I don’t want to see that happen. That’s why I’m headed to a new city, where I can work to help shape the new narrative we need and harness the tools that can bring it to life in communities across the nation.

In today’s era, where so much emphasis is given to differences, I think we might be surprised to learn just how similar these communities are. We tend to think of our city’s challenges and virtues as unique—and in some ways, they are. But moving from city to city, I am struck most by the familiarity of concerns that repeat themselves across incomes, across ethnicities, across generations.

Over the last couple years, I tried to give a voice to these concerns on this blog. While my new job will take me away from this particular privilege, I ask that you take up the torch in my absence and light the path before us to the New American Dream. Make it a path of unity, of openness, of positivity, and of respect. And no matter how difficult the path may get or how hopeless it may sometimes seem, keep moving, ever forward, until that blessed day when you finally find yourself home.