They say that twilight is the most dangerous time on the battlefield. Half day, half night, the light plays tricks on your eyes, and the time plays tricks on your body. It is in this moment of transition that you are most vulnerable to an attack.

But this battlefield transition is not the only time of transition that brings danger to our soldiers. The transition from combat to civilian life is a minefield of an entirely different variety. In many ways, this transition will be the hardest one they will ever face. And it is their decision to serve as our protectors that sets the stage for the later hardship our veterans often face.

We often forget, when we talk of their sacrifice, that the rest of us had a head start. They left just when we were going off to college or getting our first job, and by the time they came back, we had already climbed a few rungs on the ladder. They have some catching up to do—and some baggage that’s weighing them down.

How, for example, will they find a place to live?

They typically have limited savings, no job, and virtually no income or wealth. They usually don’t have a college education or a credit history or a social network of friends and coworkers and mentors to guide them. They have spent their adult years defending us. They have had no exposure to —or time forsake.—such things.

What they do have, all too often, are painful memories. They may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. They may have suicidal thoughts. Suicides, after all, claim more military lives than actual combat. They may turn to substance abuse to cope. They likely will pass these problems on to their children, and then their children are likelier to have suicidal thoughts as well. Soldiers never suffer alone. Families suffer with them. Communities suffer with them.

These are some of the reasons why veterans are more likely to be homeless than the rest of the population, why they tend to remain homeless for longer periods of time, and why they have worse health, on average, than the rest of the homeless population. The majority of veterans report that they did not receive assistance in finding a job or getting into college or securing permanent housing when they left the service. It’s a testament to their resilience (and good fortune) that over 80 percent of them didn’t wind up homeless.

But if we focus only on homelessness because it happens to be the most visible symptom, we miss millions of veterans who are just barely clinging to their homes. Here in Los Angeles, one survey found that veterans who had permanent housing “were virtually unanimous in their views that if it were not for family or friends, they would have been homeless.”

That’s why the Department of Veterans Affairs runs a home loan program. It’s why the Department of Housing and Urban Development partners with the VA to give vouchers to homeless vets with a disability. Without these programs, the problem would be much worse. Unfortunately, they’re simply not enough.

Those programs aren’t fully meeting today’s challenges. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have multiplied the number of veterans in need faster than the VA can keep up. This generation of vets is applying for VA home loans at much lower rates than their predecessors. Many of them say they don’t even know the program exists. And the HUD-VA supportive housing vouchers? They only help 50,000 vets a year.

This is not a lost cause. These brave men and women know how to thrive when they’re given a fair shot. Veterans have a higher homeownership rate than the rest of the population specifically because the last generation put the VA home loans to good use, and the number of homeless veterans has been declining as the HUD-VASH program has been expanding.

But the government shouldn’t be alone in this effort. We all owe our protectors a chance to have the American dream for themselves and their families—and history has shown that they more than pay back our faith and investment in them. When Congress passed the famous GI Bill in 1944, the veterans of World War II used the mortgages and college educations they received to build the greatest prosperity the world has ever seen.

“We all owe our protectors a chance to have the American dream for themselves and their families—and history has shown that they more than pay back our faith and investment in them.”TWEET THIS

Here at USC, we have made a similar commitment. Our president Max Nikias recently joined with retired general David Petraeus announce a program that offers full undergraduate tuition to all academically qualified veterans—and they called on other private research universities to do the same.

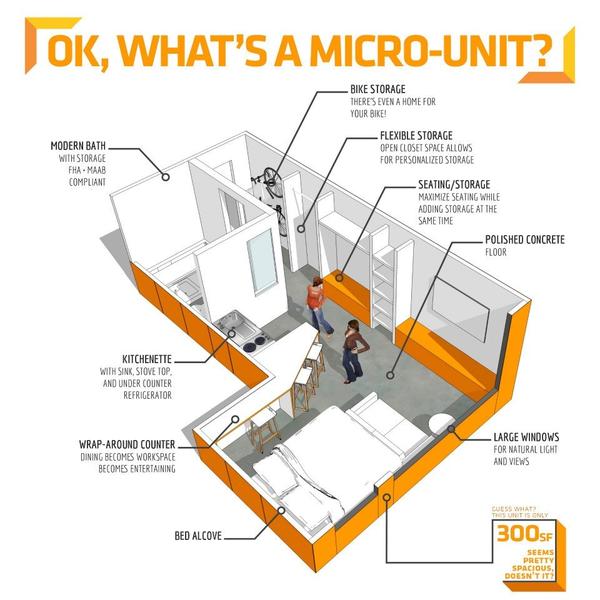

If we can do it in education, we can do it in housing. This is one reason why Home Matters has partnered with The Home Depot Foundation on the Home Today, Home Tomorrow Design Challenge – and getting a veteran into a newly designed, grow-in-place home. We need more housing grant programs like this, which provides money to build and fix up housing for veterans. We need to build as many homes as it takes to end veteran homelessness. We need to reach out to every veteran when it’s their turn to come home and make sure that’s exactly what they get. After all, we wouldn’t have our home if it weren’t for them.